It’s no secret that ergonomics programs often struggle to make an impact. All too often, they start off with a flurry of training and assessments and then fizzle out when people realize that there’s more talking about ergonomics than implementing ergonomics improvements. The ergonomics program starts to feel like more cost than benefit to management, and they reduce the resources committed to supporting ergonomics activities.

Successful ergonomics initiatives are designed from the beginning to deliver results—workplace improvements that reduce ergonomics risk while making jobs easier and less painful for workers. These ergonomics improvement programs treat training and assessments as enabling activities, not deliverables. While they set goals and monitor progress for enabling activities, the real measure of success is ergonomics risk reduction achieved through workplace improvements.

A robust approach for driving workplace improvements that reduce ergonomics risk follows the principles of risk management used in safety management systems. These systems typically focus on three steps to improve worker health and safety by reducing workplace risks:

- Identify potential issues.

- Assess the risk.

- Control the risk.

Ergonomics, unlike traditional safety concerns such as machine safeguarding or confined spaces, is not subject to specific workplace standards in most countries. Consequently, getting funding approved for ergonomics improvements is often a barrier to implementation; hence, cost justification is an important fourth step for a successful ergonomics initiative.

Another important aspect of successful ergonomics initiatives (not addressed in this article) is preventing ergonomics risk in the workplace. Risk prevention requires a systematic focus on the design and selection of products, processes, equipment, and tools. Most often, activities are conducted by the designers and engineers who drive the decisions that determine work requirements that either present ergonomics risk or provide a low-risk work environment. For information on ergonomics risk prevention, download Ergoweb’s guide 5 Essential Elements of a Successful Ergonomics Process.

1. Identifying Potential Ergonomics Issues

The first step of ergonomics risk management is to identify potential ergonomics issues. These are tasks in which workers experience a combination of forceful exertions, awkward working postures, and repetitive movements. Other issues that can arise include contact stress, vibration exposure, and temperature extremes.

Potential ergonomics issues can be identified by anyone in the workplace, from workers doing the tasks, to supervisors familiar with the jobs in their area, to health and safety professionals conducting inspections. Three basic activities are helpful for ensuring that potential issues are recognized and communicated appropriately for follow-up:

- Train workers, supervisors, and anyone else who has contact with the workplace to recognize potential ergonomics issues and how to report them.

- Develop checklists of common ergonomic issues for use during activities such as safety walks, ride-alongs, area inspections, and lean production activities such as 5S or 3P.

- Establish straightforward methods for reporting potential ergonomics issues—multiple methods are recommended as communication preferences vary.

A couple of advanced recognition activities, not recommended until your ergonomics improvement process has resulted in sustained results and demonstrated an impact, include:

- Systematically screen all jobs with a checklist of common ergonomics issues.

- Survey all workers to identify tasks that they find uncomfortable or demanding.

While it may seem intuitive that these advanced recognition activities are a good idea, experience has shown that they can strain the resources of a developing ergonomics improvement program and be counterproductive if done too early. Start with the basic recognition activities and address the potential ergonomics issues that they identify before launching advanced recognition activities that require substantial resources and can produce an overwhelming number of potential issues requiring follow-up.

2. Assessing Ergonomics Risk

The second step of ergonomics risk management is to assess potential ergonomics issues and determine if the tasks present a high risk for musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs). This step helps identify root causes of the ergonomics risk, important in Step 3 (Controlling Ergonomics Risk) below. There are a variety of ergonomics assessments available, ranging from screening surveys that provide a risk score for a job to deep-dive analysis tools that quantify ergonomics risk of a specific type of task.

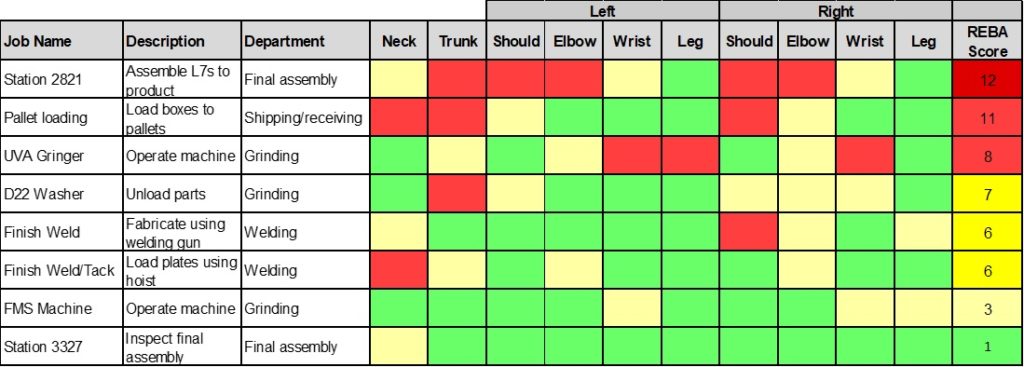

Ergonomics screening surveys score the presence of ergonomic risk factors at different threshold levels. These are typically used to prioritize where improvement efforts should go based on the score and the number of people impacted by the job. An ergonomics risk map can be developed that clearly shows the jobs that present the highest ergonomic risk exposures. The Rapid Entire Body Assessment (REBA) and Rogers/Kodak Muscle Fatigue Assessment are examples of ergonomics screening surveys.

Deep-dive ergonomics assessments are specific to a type of activity. They typically provide a complex mathematical formula to determine how hazardous a task is but don’t address all the ergonomic risks in a job. In many cases, deep-dive assessments are suited for either manual material-handling tasks or intensive hand and arm work. Some examples of deep-dive ergonomics assessments include:

| Deep-Dive Assessment Tool | Applicable Tasks | Primary Body Regions Addressed |

| 2D Static Biomechanical Model | Lifting/lowering and pushing/pulling | Back, leg, shoulder, elbow |

| ACGIH Upper Limb Localized Fatigue | Hand- or arm-intensive tasks | Hand/wrist, elbow, shoulder |

| Liberty Mutual Push-Pull Guidelines | Pushing and pulling | Back and shoulder |

| Revised NIOSH Lifting Equation | Lifting and lowering | Back |

| Strain Index | Hand-intensive tasks | Hand/wrist |

Figure 2. Examples of Deep-Dive Ergonomics Assessment Tools

Companies have had success training professionals outside of the health and safety function to conduct ergonomics screening surveys. However, deep-dive ergonomics analysis tools require advanced skills and are typically completed by ergonomists or health and safety professionals with advanced training in ergonomics.

3. Controlling Ergonomics Risks

Reducing ergonomics risk through workplace improvements is the third step in ergonomics risk management. However, successful ergonomics improvement programs typically include a fast-track process for implementing improvements in Step 1 (Identifying Potential Ergonomics Issues). Oftentimes, a simple, low-cost solution to a potential issue is fairly obvious, and it makes sense to implement the solution—as long as everyone agrees to it—without formally assessing the ergonomics risk.

The most effective ergonomics controls are engineering controls—changes to workplace conditions that reduce ergonomics risks. Engineering controls focus on permanently limiting exposure to ergonomic risk factors, while other types of controls rely on worker behaviors. According to OSHA, “Administrative or work practice controls may be appropriate in some cases where engineering controls cannot be implemented … ” (https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/ergonomics/controlhazards.html). Examples of administrative and work practice controls include rotating jobs, setting weight limits for manual lifting, and training workers in techniques to reduce stress and strain.

Examples of engineering controls include changes to workplace geometry, material movement, tool design, and part presentation. Typically, engineering controls are targeted at eliminating or reducing specific ergonomic risk factors, such as forceful exertions, awkward working postures, repetitive movements, contact stress, exposure to vibration, or temperature extremes. A creative problem-solving process that begins with a clear problem definition (specific ergonomic risk factors to reduce) and includes input from workers doing the job is often used to identify the best ergonomic improvements. When possible, low-cost improvements should be emphasized to avoid the need to justify investments.

4. Justifying the Cost of Ergonomic Improvements

Ergonomics improvements that require expenses over a certain threshold (which is unique to each company) are often required to satisfy cost justification analyses. The challenge is that, oftentimes, costs related to injuries, turnover, and worker morale are not fully accounted for in the benefits analysis, so ergonomics improvement projects are often not funded due to lack of cost justification. Some companies address this by requiring a lower return-on-investment threshold for ergonomics improvements, but in other companies, ergonomics is held to the same threshold as other projects.

The good news is that while ergonomics improvements are usually initiated to reduce injuries and worker discomfort, they often improve productivity and quality as well. If an ergonomics improvement reduces reaching or walking distances, eliminates manual tasks, or allows a two-worker job to be performed by one worker, productivity improvements can be quantified and may be sufficient to justify the investment. Likewise, if quality issues are occurring, cost of quality can be calculated and used as part of the investment justification. The specific methods for quantifying the economic benefits of increased productivity and improved quality are specific to each company. An example of an ergonomics improvement project cost justification is summarized below.

| Ergonomics after 10 years: $1.9M annual benefits vs. $495K overall costs

A 100-person die-casting plant invested $495,000 over 10 years to improve the ergonomics of operations. The company pursued a lean manufacturing strategy with a focus on reducing manual handling requirements. Ergonomic improvements affected virtually all jobs in the facility over 10 years. Most improvements were low tech and based on discussions with employees. Outcomes included:

Click here to view the full case study. |

Figure 3. Example of Ergonomics Improvement Project Results

Mike Wynn is Vice President of Ergoweb, a software company that, for over 20 years, has helped companies create sustainable ergonomics programs. He has consulted with hundreds of companies since 1989 and, in that time, has served on ergonomics committees for the American Industrial Hygiene Association, Applied Ergonomics Conference, and National Ergonomics Conference. Mike’s focus at Ergoweb is understanding user needs for ergonomics management software and translating those needs to the capabilities of Ergoweb Enterprise, its simple and adaptable software platform. E-mail him at mike.wynn@ergoweb.com or visit www.ergoweb.com. Mike Wynn is Vice President of Ergoweb, a software company that, for over 20 years, has helped companies create sustainable ergonomics programs. He has consulted with hundreds of companies since 1989 and, in that time, has served on ergonomics committees for the American Industrial Hygiene Association, Applied Ergonomics Conference, and National Ergonomics Conference. Mike’s focus at Ergoweb is understanding user needs for ergonomics management software and translating those needs to the capabilities of Ergoweb Enterprise, its simple and adaptable software platform. E-mail him at mike.wynn@ergoweb.com or visit www.ergoweb.com. |