The hazard communication standard (29 CFR 1910.1200)—sometimes referred to as the HazCom standard or “worker right-to-know”—remains one of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) most frequently cited standards.

The HazCom standard was the second most frequently cited workplace safety standard for fiscal year (FY) 2020, with 3,199 violations. The construction industry fall protection standard (§1926.501) was the most frequently cited standard, with 5,424 violations. FY 2020 ended on September 30, 2020.

Industries frequently cited for HazCom violations include accommodation and food services, construction, manufacturing, waste management and remediation services, and wholesale trade.

Other standards frequently cited in manufacturing facilities include control of hazardous energy (lockout/tagout), forklifts, machine guarding, and respiratory protection.

Employers must have a written HazCom program to meet requirements of the standard. A written HazCom program establishes all aspects of the program, like the use of labels and safety data sheets (SDSs) and employee information and training. Employers must provide employee access to SDSs in addition to training on understanding the hazard and precautionary information contained in labels and SDSs.

In addition to training on labels and SDSs, a compliant HazCom training program would need to cover:

- Methods used to detect the presence or release of a hazardous chemical in a work area;

- Hazards of chemicals in the workplace, such as asphyxiation or health hazards, combustible dust, and physical hazards like explosiveness, flammability, or reactivity, as well as some hazards not otherwise classified; and

- Measures employees can take to protect themselves from these hazards, including specific procedures the employer has established to protect employees from exposure to hazardous chemicals like emergency procedures, routine work practices, and personal protective equipment (PPE) to be used.

Agency inspectors will review the written program during a workplace walkaround, confirming that the program includes a complete inventory of all hazardous substances; methods for informing employees of hazards encountered in both routine and nonroutine tasks and the hazards of substances in unlabeled pipes; and methods for informing other employers’ employees at multiemployer worksites, such as whether all workers at a facility or site know how to access information about the program.

Epidemic Adds a HazCom Wrinkle

The scope of worker right-to-know expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic, as OSHA employer guidance included cleaning and sanitation guidelines recommending the use of disinfectants on the EPA’s “List N” of Disinfectants for Use Against SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). State emergency temporary standards (ETSs) for COVID-19 also included cleaning and sanitation requirements.

Some disinfectants on the EPA’s list have health or flammability hazards. OSHA’s HazCom standard requires that employees be informed of potential work hazards and trained in safe practices, procedures, and protective measures for chemical hazards. Employers must ensure employees have access to cleaning products’ SDSs and are informed of potential hazards and trained in safe handling and use practices detailed in the products’ SDSs.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) last summer alerted employers that employees need to be informed of documented health risks from exposure to specific cleaning ingredients such as acetic acid, hydrogen peroxide, and peracetic acid. Employers need to maintain sufficient ventilation in areas where chemicals are used and ensure that employees use appropriate protective clothing, gloves, or safety goggles.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported that the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission from surfaces is low, but cleaning and disinfection guidelines and requirements remain in place.

HazCom, GHS

HazCom, GHS

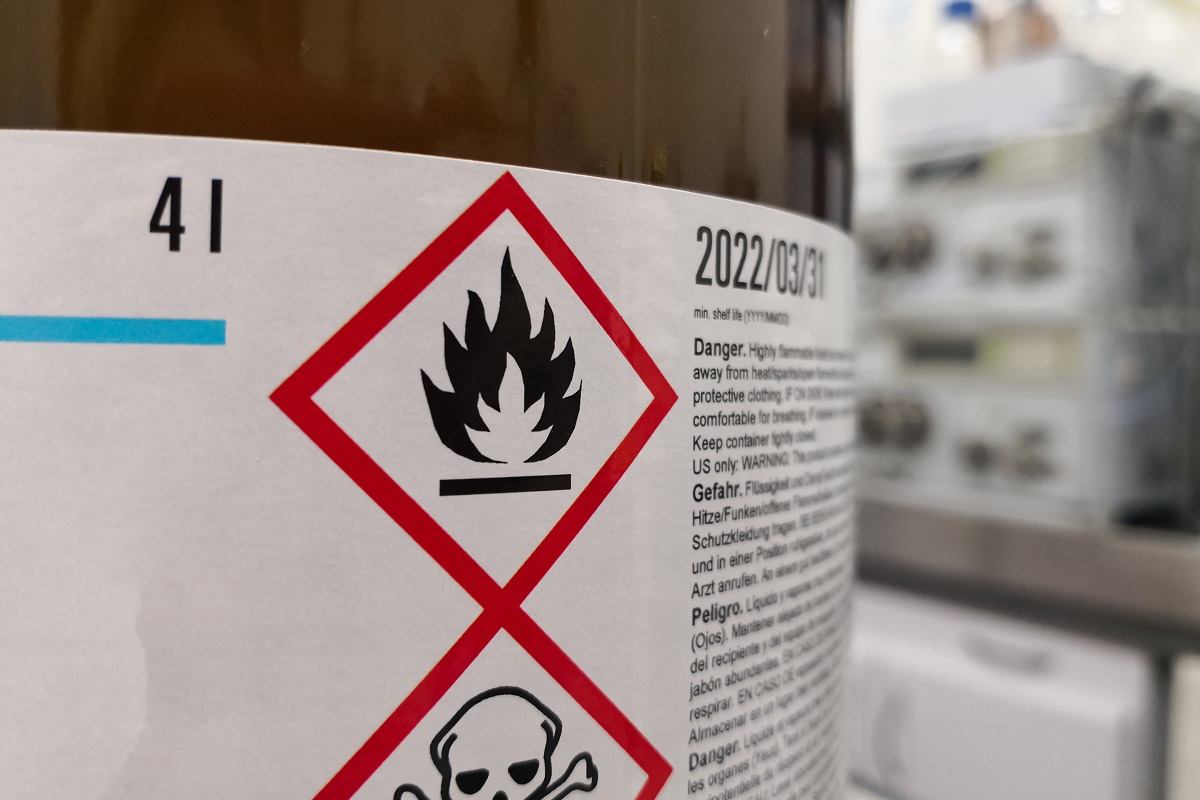

The HazCom standard has been aligned with the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS), an international agreement for uniform regulation to ease the trade and transportation of chemicals. However, the HazCom standard usually conforms to an earlier edition of the GHS due to quirks of U.S. administrative procedures. For example, OSHA recently extended the public comment period for a proposed update to the HazCom standard, aligning provisions of the rule with the seventh revision of the GHS published in 2017. An eighth revised edition was published in 2019.

Updates in the seventh edition of the GHS included:

- Revised criteria for categorization of flammable gases within Category 1;

- Miscellaneous amendments intended to clarify the definitions of some health hazard classes;

- Additional guidance to extend the coverage of section 14 of the SDSs to all bulk cargoes transported under provisions of the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), regardless of their physical state;

- Revised and further rationalized precautionary statements in Annex 3; and

- A new example in Annex 7 addressing labeling of small packages with foldout labels.

OSHA’s HazCom standard proposal would implement substantive changes for chemical manufacturers and importers, amending the requirements for the labels and SDSs that manufacturers and importers must provide for hazardous chemicals in commerce. The proposed amendments would alter the content of the labels and SDSs that employers receive and necessitate updating their SDS collections.

The proposal would allow manufacturers to guard their chemical trade secrets by reporting a range of chemical concentrations on their SDSs. Canadian regulators already have adopted the SDS ranges of concentration.

Inspection, Enforcement Procedures

During OSHA inspections, agency compliance safety and health officers (CSHOs) will check that employers have developed a written HazCom program covering all employees who may be exposed to hazardous substances. The program must include information and procedures for labels and other warnings, SDSs, and training used in the workplace.

Under OSHA’s inspection procedures, CSHOs also check for a complete and current collection of SDSs for all substances in the workplace, the person designated as responsible for SDSs, how SDSs are maintained (electronically or in a notebook) and how employees can access them, procedures used when shipments do not include SDSs, and whether workers are trained in the format and use of SDSs.

In a multiemployer workplace, a CSHO will look at how other employers’ employees can access SDSs for substances on-site and how they are informed of and trained on chemical hazards in the workplace and necessary precautions. Agency inspectors expect both host employers and employment agencies to take responsibility for HazCom. CSHOs may cite both if an employment agency’s workers are not informed about and trained in hazards of chemicals used at the workplace.

CSHOs also will check for the person responsible for label compliance, appropriate labels on all containers in the workplace, descriptions of alternative labeling methods used for stationary process containers, descriptions and explanations of labels used in or shipped through a workplace, and procedures for reviewing and updating labels.

Additionally, CSHOs also will look into elements, formats, and procedures of the training program, as well as the person responsible for training. Inspectors may cite an employer for the lack of a written program, as well as all the missing elements of a program, like the absence of labels and SDSs or a training program. Agency inspectors issue nearly as many citations for information and training violations as they do for lack of a written program.

For example, the agency cited a Pennsylvania manufacturer for willful violations of the HazCom standard and sought $94,753 in proposed penalties. Inspectors concluded that the employer failed to train employees in methods and observations to detect the presence of hazardous substances; health and physical hazards of the substances in their work areas; work practices, emergency procedures, and PPE intended to protect employees from exposures to hazardous substances; and labeling systems and SDSs used in the employer’s HazCom program.

Other employers have been cited for violations that include:

- Failing to compile a list of hazardous substances in the workplace, label a dip tank containing a flammable liquid, maintain workplace copies of SDSs, and provide employee training on hazards in the workplace and details of the company’s HazCom program;

- Serious violation of the HazCom standard for failing to provide information and training on brake cleaners, silica, solvents, and other hazardous substances used at a concrete production plant; and

- A serious violation for failing to ensure containers of hazardous substances were properly labeled, tagged, or marked and failing to provide information and training at the time of initial assignment or whenever a new substance was introduced into a work area.

The Bigger Picture

The HazCom standard is one piece of a bigger chemical regulation scheme that also involves the EPA and the Department of Transportation’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA). Each has its own regulatory authority during various points of the transport, storage, use, and disposal of hazardous substances. Chemicals go through an assortment of information, labeling, and placarding requirements as they move through the supply chain and eventually end up as waste products.

Outlines of the chemical regulation scheme include:

- The PHMSA sets and enforces hazmat transportation regulations under the Hazardous Materials Transportation Act of 1975 (HMTA), which conform to the United Nations’ UN Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods (the “Orange Book”), a model regulation of standards for containers, packages, and placards used for hazmat transportation.

- OSHA’s HazCom standard, which regulates chemical safety in the workplace and incorporates elements of the GHS.

- The EPA regulated hazardous waste disposal under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), although OSHA regulates the health and safety of workers through its Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response (HAZWOPER) standard.

Even the nongovernmental National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) has its own set of chemical hazard symbols. At various points in the supply chain, a container could display a DOT Hazmat placard, an NFPA “fire diamond,” and an OSHA label.

The NFPA developed and maintains the industry consensus standard (NFPA 704) for labeling containers, tanks, and facilities to alert firefighters and other first responders to fire, health, and other hazards. An NFPA fire diamond is separated into blue, red, and yellow quadrants to communicate health, flammability, and instability hazards, as well as a fourth white quadrant with special warnings. The white quadrant warns firefighters whether a substance is an asphyxiant gas or an oxidizer or reacts with water.

Information about the health, flammability, instability, and special hazards displayed in a fire diamond also would be included in sections of an SDS required by the HazCom standard.

Remember that HazCom compliance is not “one and done” but an ongoing responsibility. Your written HazCom program is the cornerstone of compliance and needs to cover how you will handle labels and other warnings, SDSs, and employee information and training.