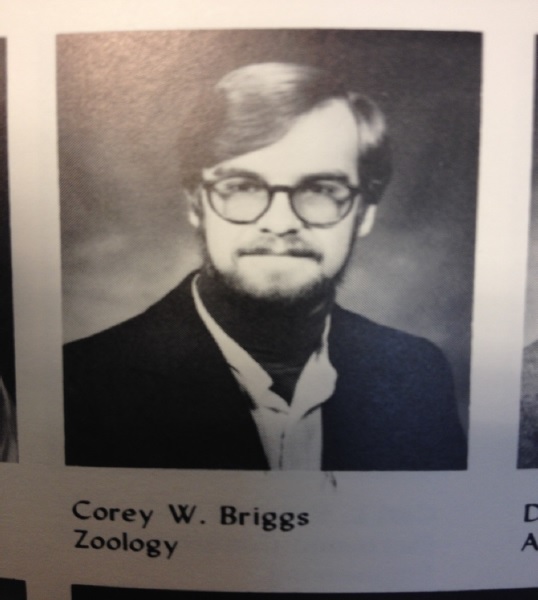

Corey Briggs, a Senior Consultant at Colden Corporation, has been involved in the field of environment, health, and safety (EHS) for more than 38 years. In a special Safety Stand-Down Week “Faces of EHS” profile, read about Briggs’s fascinating career across multiple industries, which includes his beginnings as an undergraduate zoology major, work in industrial hygiene, conducting over 1,000 EHS audits, and chemical spill emergency response, and even providing training for federal, state, and local law enforcement personnel on how to safely deal with meth labs.

We’ll start out with the basics. What led you to pursue a career in EHS?

We’ll start out with the basics. What led you to pursue a career in EHS?

When I was an undergraduate at the University of Rhode Island back in the mid-’70s, I was a zoology major and wanted to be a marine biologist. Everybody wanted to be a marine biologist because Jacques Cousteau was on TV once a month, and it felt like, “Oh, this is going to be cool; we’re going to get to swim, do stuff, and get paid for it.”

Then I started investigating a little bit more. Marine biology was very interesting and we had some pretty bad oil spills up here in the Cape Cod area. While I was studying invertebrates, clams, oysters … I started spinning this idea in my head of something like pollution control and water quality. I got my degree in zoology, but I also took marine affairs and some civil engineering classes. I got my BS in zoology but really built a “hybrid degree,” knowing that the chance to be a marine biologist was now pretty slim.

So, I got my degree and was fortunate to get a grant from the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS). This was back when the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) and USPHS had money and they would provide grants for students to go to graduate school. I tried to get into grad school for marine biology—me and 85,000 other people trying to apply for maybe two slots at certain universities. I got in at University of South Carolina, but it wasn’t for marine biology; it was for something called environmental health science, and they had a “water quality emphasis.” I said, “OK, yeah, that could be good.”

At the time, jobs were slim and not paying a whole heck of a lot, and I started learning a little bit more about industrial hygiene (IH), and USC had an IH sub-track. Amazingly, my sister was also in IH—she’s since retired—and was a certified industrial hygienist (CIH) and certified safety professional (CSP). We didn’t talk about her work, but I knew what she did, and as I started getting more and more into the curriculum, I thought, “This is interesting, this fits my personality, and this fits my attention span. And I don’t like to be doing the same thing every day.” And that’s how I got from marine biology over to IH and EHS—it was all fortunate timing in a really, really good program at South Carolina. That’s where it started. From there, my career has gone all over the place.

Your current organization does a lot of consulting work, correct?

Yeah, Colden Corporation is a consultancy, and we’ve been in the business 25 years. We’re small and primarily located in the Northeast. We consult on health, occupational health and safety, occupational health science, IH, and the like. My days of doing environmental work, air work, water work, and waste site work are in the past. I’m pretty much on the sunset of my career right now, so I wanted to go out working with a firm that focused on industrial hygiene and OHS. The cool thing about consulting is that perhaps one day, I’m at a safety site; the next day, I could be doing an indoor air quality evaluation; the next day, I could be doing training; the next day, I could be doing an inspection; and the next day, I could be writing reports. Or all of that could happen within a day or 2. We’re never really bored.

What has been one of the biggest EHS compliance or IH compliance challenges (from your time at Colden or earlier your career) that a client has brought to you, and how did you help them manage that challenge?

Wow. One of the biggest?

Well, maybe not the biggest but something interesting—or weird.

OK, I’ve done some pretty weird things. From 1999 through about 2004, I was a DEA clandestine drug lab trainer subcontracting to NES, Inc. from Folsom, California, and was training federal, state, and local law enforcement on how to safely recognize, evaluate, and control hazards around illegal methamphetamine labs. We would go down to the DEA training field office in Quantico, Virginia, and undercover people would come in, and basically, it was like … I called it HAZWOPER for cops. That was interesting because for part of my career, I did emergency response to chemical spills and hazardous waste site work. And I mean did it. I wasn’t the health and safety guy on-site; I was there pitching in on actual cleanup. I’ve been on 250,000-gallon sulfuric acid spills—and that’s big. And then you start talking about meth labs, and people are making bad stuff with household chemicals that they get at Home Depot or stuff from under the kitchen sink, and they create a whole other type of emergency response. That was wild.

Another weird one was back in my earlier days when I worked with a company called IT Corporation. It was one of the big guns back in the late ’70s, early ’80s. Emergency response, hazwaste sites, EPA contracts—we had disposal sites where we got this one wacky contract with a major chemical company. I won’t mention the name because it’s not in business under that name anymore. But this was after a very large environmental episode that occurred in the world called Bhopal.

Another weird one was back in my earlier days when I worked with a company called IT Corporation. It was one of the big guns back in the late ’70s, early ’80s. Emergency response, hazwaste sites, EPA contracts—we had disposal sites where we got this one wacky contract with a major chemical company. I won’t mention the name because it’s not in business under that name anymore. But this was after a very large environmental episode that occurred in the world called Bhopal.

So, we were hired to escort railcarloads of a nasty chemical from Louisiana to the Houston area and sometimes up to West Virginia. And the escort was as follows: We would have a team, and we would have two people who sat at a caboose behind the train. Behind the caboose, there would be buffer cars, and then the cars of the chemical, and then buffer cars, and then the real caboose.

So we are in the train that’s carrying the stuff with communications gear, some initial response gear, and things like that. And then escorting us, supposedly in close proximity, was a converted 40-foot motor home that they made into a HazMat response vehicle command and communication post—we called it “The White Whale.” And the whole concept was, the rail line matches the road line, and we just stay in contact, and if something happened, we get off the train, we’d set up an initial command area (hopefully not getting incinerated), then we would reach out, and then the command vehicle would start making notifications to agencies and get that ball rolling, and then we would convene together and figure out what to do. Sometimes, a trip to Kanawha Valley was 4 days, so you rotate people because it’s rough sitting in a railcar caboose behind a locomotive sucking in diesel exhaust. Well, nothing ever happened, which was good. But one day …

One of the corrective actions we were told was that if there is a spill or a leak, you were to take a flare gun, and you should shoot a flare into it because it was so flammable, and it would just incinerate. So one day, we’re doing training, a little mock drill, and I asked if anybody had ever shot the flare gun before. Nope. So, we take out this little flare gun like you get for a boat. Flare guns you normally shoot up, but we can’t shoot up—we have to shoot over. We fire the flare, and it goes off like 30 feet—and I say, “Well, we’re just officially incinerated now.” We realized that our flare gun was not going to go the 300, 400, or 500 feet that we needed it to go if we ever planned to use it.

Long story short, we got a bigger flare gun. But that was something like 2 years into the job. That was probably one of the wackier things among so many other weird things that I have done in EHS.

With all of these interesting challenges that you’ve worked with, are there any points that you think could prove instructive to other EHS professionals who maybe haven’t had some of these broader experiences?

Be flexible—you have to go in with an open mind. You can’t go into a problem thinking you got the solution already. One thing I’ve learned over the years is you must ask a lot of questions. My wife calls me “the 2-year-old”—I’m 63 years old, and I’ve been in this for years, but I’m still 2. And it’s because I’m constantly asking “Why?” Why do you do this, and how do you do it? You need to get respirator fit tested? OK. Why? What’s the dust? It starts out as one thing, but sometimes it becomes a bigger thing, but we have to look at the bigger thing to figure out how we’re going to get to the end point and solve your problem.

Also—and this is especially important for students coming out into the professional world—you need to know a little bit about a lot of things. The days of the pure environmental person, the pure safety person, and the pure industrial hygiene person are waning. There are going to be some around, but the majority of them are going to become EHS people. So, be flexible on that, and also be flexible in your profession.

And the other thing you have to be conversant in is the whole tie-in with management. You’ve got to understand management language. What’s a budget, and what are deliverables, outcomes, or whatever the terminology is—you have to understand and find that happy balance of what we need to get done and where compliance and where risk is and find that nice balance. I’ve told people numerous times, “If we did everything according to the rules, nothing would get done.” We wouldn’t get to where we’ve gotten without people blowing things up; we wouldn’t have a helicopter on Mars getting ready to fly unless somebody said, “Gee, I think I can do that.”

That’s the summary: flexibility, open mind, toolbox of skills, and having some management insight. You’re going to interact with management, so you have to understand where they’re coming from and how it balances out what you’re doing now.

You just mentioned EHS students—you’re active in teaching, service, and academia. How has that shaped your approach over the years?

I got into academia back in 2013; it’s getting to that point in my career where I want to give back. My program at University of South Carolina went away—they have a school of public health, but they don’t have an IH track anymore. Several years ago, a lot of the major schools lost the IH programs because there was no interest. And one of my biggest concerns right now is the lack of young people getting into the profession. The IH profession is shrinking. Environmental and safety, you’re still going to have kids who are going to be into that, but there are certain specialties that the profession has not done a good job of promoting.

I went back to my undergrad alma mater, the University of Rhode Island, where now, there’s this school called the College of the Environment and Life Sciences (CELS). Basically, its curriculum is something that I probably should have had 40 years ago. I got some very, very small amount of funding, and I got some local friends who were IHs, safety pros, and environmental people, and we formed a team. And we did the class for nothing the first year. It went over big, and we’re on our 8th year now, and eventually, I became an adjunct professor. The whole idea was just to get students thinking about the environmental field. And I’m not just saying the outdoor ambient environment—we’re talking about indoors, which can have just as many issues as the outdoors.

I went back to my undergrad alma mater, the University of Rhode Island, where now, there’s this school called the College of the Environment and Life Sciences (CELS). Basically, its curriculum is something that I probably should have had 40 years ago. I got some very, very small amount of funding, and I got some local friends who were IHs, safety pros, and environmental people, and we formed a team. And we did the class for nothing the first year. It went over big, and we’re on our 8th year now, and eventually, I became an adjunct professor. The whole idea was just to get students thinking about the environmental field. And I’m not just saying the outdoor ambient environment—we’re talking about indoors, which can have just as many issues as the outdoors.

Over the years, we’ve been doing more and more and more, trying to get students exposed to the outside world and what it’s like out there in the working world. So I tell them, “I’m going to be your professor. I’m not a PhD, so don’t call me doctor. I’m going to be your boss for the semester, not your prof. I’m your boss. I’m going to treat you like you could be treated in the real world because I want to prepare you. The working world is a great place, but if you think school is hard, the working world can be very, very, very hard.”

Over the past couple of years, with the COVID situation, we had to get very, very, very creative. I have a class 1 night a week for 3 hours—an elective. And we had to think creatively. Different guest speakers, socially distanced gear bags, remote learning—we did it all: personal protective equipment (PPE), respirator demos, and even decontamination from the comfort of your home.

Speaking of COVID, in your opinion as an IH, is there anything that is missing currently in some of the broader discussions on managing COVID-19 in the workplace?

Obviously, there’s a lot of learning on the fly. Should this have happened the way it did? No. We had a whole Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) playbook from 2007 on dealing with SARS and MRSA. I’m still wondering, when all is said and done, why didn’t we go to this playbook? We had been through this, we kind of knew this was going to happen, and we still got caught unprepared. It’s akin to you not wanting to pay into an insurance policy and instead saying, “I’m going to take a chance.”

But if you had paid the insurance policy, that money is there to help you—well, money, resources, whatever. We didn’t put into the policy, and now we’re paying for it, and a lot of people paid dearly for it. But there are still a lot of unknowns right now that we’re walking through even as people are getting vaccinated. Well, guess what? We’re dealing with a biological. We’re dealing with a lot of unknowns, and people don’t like unknowns; people like black and white, but sometimes, we can’t have that level of certainty.

I feel for the economy, but as a public health person, I’ve been very, very, very frustrated the past year and a half. I just can’t comprehend why somebody, anybody, let alone 40,000 people, would want to go to a baseball game right now. Yes, it’s risk management, and I’m getting on a soapbox. I really don’t want to, but it’s a worldwide issue. And when you have worldwide issues, in order to correct them, sometimes your individual choices may have to take a backseat. I go back to World War II, even though I was not around for that. If you’ve never been, go down to the WWII Museum in New Orleans. It is jaw-dropping. You see the Pacific Theater, and you see the European Theater, but you also see what people had to give up back in the United States, back in their respective communities that weren’t part of the combat scene, and you’ll think, “Holy mackerel.” Imagine pulling that off nowadays. We’re getting people complaining because they don’t want to wear a mask. Back then, you’re not going to have tires on your car. Or you can have one cracker a day. “Who’s telling me I can’t have more than one cracker a day?” The war effort. And this situation now has been like a war against the virus. It’s just as society changes, people change. I hate to say it, but it’s turned into a “me” society versus an “us” society, which is not good. We’re not going to move forward one at a time.

We hope that something’s going to come out of this—that we learn from our past mistakes or that we can be better prepared. There are going to be papers and papers and studies and studies that are going to come out of this for years. But I think as a scientific community, we’re doing the best we can. The biggest thing, right off the bat, is that we should take politics out of science, but we can’t do much about that. We’re too connected a world. And we’re paying for some past mistakes. One thing we try to do is learn from our mistakes, so that’s what we’re trying to do, and keep moving forward, and we’re going in the right direction. That’s a good thing.

What do you see as some of the main emerging trends, positive or negative (or both), that are affecting the future of the profession?

It’s staffing, which we touched on a bit earlier—getting students interested in EHS and in career opportunities both public and private. Why? Well, I think one of the downfalls that occurred way back is that many graduates would ask themselves, “Why do I want to do this? I can go to Wall Street and make 150 grand with a bachelor’s degree, with a bonus of 100 grand.” So where did everybody go? They flocked to the business sector. Some of them may have made it, but some of them didn’t.

I’ve heard and also told people that in order to get into this field, you have to have some passion. You have to be interested in helping people and communicating on tough issues, understanding that you’re probably not going to get your way all the time. You’re still going to make a decent living, and you’re going to have an impact on people. And there are all sorts of opportunities.

It was 100+ years between the start of the Industrial Revolution and the EPA and OSHA being created in 1970, and we’re still playing catch-up—and probably always will be. We were talking about PFAS a few days ago. We created these substances that were everywhere, except we didn’t know what the toxicity was going to be. And now, guess what? Your water supply 10 years from now? Hey, you may not be able to use it anymore. We’ve got to figure out how to do things in moderation. This Earth is finite.

And playing catch-up is hard when you’re left out of the conversation. I still run into EHS folks who aren’t brought into daily meetings at their facilities to find out what’s happening, what’s coming in, or what’s the new product or the new chemical. They always find out on the back end when problems are going to happen. And if you’re on the back end of getting information, all you’re going to be doing is firefighting, not being proactive, which is where we should be.

So, what advice do you have for people just now entering EHS or IH as a career?

One, you’re not going to be in charge after a year, as much as you think you might be. Two, listen. Three, listen. And four, listen. If you have some experience in something and you can share it, share it. If you don’t know something, don’t share it—think about it first because what you bring up may just confuse things. Also, I tell people who come to work for me, especially right out of school, don’t agree with me just for the sake of agreeing or just to get onto the next thing. I want you to listen, and if something didn’t make sense, you have to let me know.

Be prepared. I have a whole list of things when I do presentations for students. Being organized is key in your thinking and in your material organization. Good communication, written and verbal. You have to be a good communicator. One big thing I hear from clients is that young folks’ writing skills are horrible. And I’m not just saying writing skills in the sense of stringing words together; I mean actually writing. My handwriting is horrible, but I recall one young candidate’s was about three levels worse. He was filling out a chain of custody they sent to the lab, and they couldn’t read it, and so they call me up. And I say, “I can’t even read it.” So, I call him up. He says, “I don’t know what I wrote.” Well, the handwriting really needs some work there. I’m not asking you to be like John Hancock. Just take your time and print things out. So, I don’t know what the schools are doing, and that’s why I’ve tried to get back to the university and engage with students and professors alike with not just new ideas but also the basics.

Finally, be patient and continue to move forward. In the context of COVID, which is a good example, I told my students that, yes, this past year was horrible, and it was miserable, but we’ve got to move forward. We can’t live in the past. We’ve learned from our mistakes, so we’ve got to move forward. I encouraged them to not get frustrated by the job market. Things are going to pick up. Things that weren’t getting done the previous 4 years in EHS are now going to get done again. Somebody’s got to do them.

| Corey Briggs, a Senior Consultant in Colden Corporation’s Boston area office, has been involved in the field of EHS for more than 38 years. He focuses on assisting clients with technical and management problems related to IH/workplace exposures; employee, facility, and process safety; loss prevention and emergency response; and training and education. He has extensive experience auditing, evaluating, and developing a wide variety of EHS program elements and developing and presenting employee training seminars. He has provided consulting services around the world to pulp and paper; aerospace; specialty chemical; petrochemical; pharmaceutical; electric utility; manufacturing; food; financial institutions; insurance companies; real estate/property management companies; and federal, provincial, state, and local government agencies.

Briggs has an MSPH in Environmental Health Science from the University of South Carolina and a BS in Zoology from the University of Rhode Island. He is an American Board of Industrial Hygiene (ABIH) CIH; a National Environmental, Safety, and Health Training Association (NESHTA) Certified Environmental Trainer; and an American Industrial Hygiene Association (AIHA) fellow. Briggs is also a past president and board member of the New England section of the AIHA and is a regular presenter of professional development seminars for national and local sections of the AIHA, the American Society of Safety Engineers (ASSE), and other health and safety organizations. Briggs is an Associate Adjunct Professor in the Department of Geosciences in CELS at the University of Rhode Island and an Adjunct Professor at the Massachusetts Maritime Academy and is a guest lecturer at the Harvard School of Public Health. He previously held various positions with other major consulting firms, IT Corporation, and the South Carolina Public Service Authority/Santee Cooper. |

Would you like to be profiled in a future “Faces of EHS” and share your experiences, challenges, etc.? Or, do you know anyone else in EHS you think has an interesting story to tell? Write us at ehsposts@SimplifyCompliance.com, and include your name and contact information; be sure to put “Faces of EHS” in the subject line.